Fenian

The word Fenian (/ˈfiːniən/) served as an umbrella term for the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and their affiliate in the United States, the Fenian Brotherhood. They were secret political organisations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries dedicated to the establishment of an independent Irish Republic. In 1867, they sought to coordinate raids into Canada from the United States with a rising in Ireland.[1][2] In the 1916 Easter Rising and the 1919–1921 Irish War of Independence, the IRB led the republican struggle.

Fenianism

[edit]Fenianism (Irish: Fíníneachas), according to O'Mahony, embodied two principles: firstly, that Ireland had a natural right to independence, and secondly, that this right could be won only by an armed revolution.[3] The name originated with the Fianna of Irish mythology—groups of legendary warrior-bands associated with Fionn mac Cumhail. Mythological tales of the Fianna became known as the Fenian Cycle.[4]

In the 1860s, opponents of Irish nationalism within the British political establishment sometimes used the term "Fenianism" to refer to any form of mobilisation among the Irish or to those who expressed any Irish nationalist sentiments, or questioned the Protestant Ascendancy (such as by advocating for the rights of tenant farmers). The political establishment often applied the term in this sense—inaccurately—to the unrelated Tenant Right League, the Irish National Land League and the Irish Parliamentary Party, who did not advocate explicitly for an independent Irish Republic or for the use of force.[5][need quotation to verify]

Ireland

[edit]

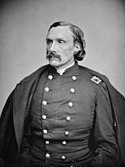

James Stephens, one of the "Men of 1848" (a participant in the 1848 revolt), had established himself in Paris, and was in correspondence with John O'Mahony in the United States and other advanced nationalists at home and abroad. This would include the Phoenix National and Literary Society, with Jeremiah O'Donovan (afterwards known as O'Donovan Rossa) among its more prominent members, which had been formed recently at Skibbereen.

Along with Thomas Clarke Luby, John O'Leary and Charles Kickham he founded the Irish Republican Brotherhood on 17 March 1858 in Lombard Street, Dublin.

The Fenian Rising in 1867 proved to be a "doomed rebellion", poorly organised and with minimal public support. Most of the Irish-American officers who landed at Cork, in the expectation of commanding an army against the British, were imprisoned; sporadic disturbances around the country were easily suppressed by the police, army and local militias. In the aftermath, Fenian assassination circles were active in Cork and in Dublin and were responsible for shooting two officers of the Dublin Metropolitan Police on duty in October 1867.[6]

In 1882, a breakaway IRB faction calling itself the Irish National Invincibles assassinated the British Chief Secretary for Ireland Lord Frederick Cavendish and his Permanent Under-secretary (chief civil servant), in an incident known as the Phoenix Park Murders.

United States

[edit]The Fenian Brotherhood, the Irish Republican Brotherhood's US branch, was founded by John O'Mahony and Michael Doheny, both of whom had been "out" (participating in the Young Ireland rebellion) in 1848.[7] In the face of nativist suspicion, it quickly established an independent existence, although it still worked to gain Irish American support for armed rebellion in Ireland. Initially, O'Mahony ran operations in the US, sending funds to Stephens and the IRB in Ireland.

In 1865, O'Mahony's leadership was challenged and the movement was split by a faction led by William B. Roberts, a wealthy New York City dry-goods merchant, more closely allied with the Democratic-Party machine. It was Roberts' faction that sponsored the plan to invade Canada and hold it hostage for the liberation of Ireland.[8] In 1867 there was a further challenge to O'Mahony from the new IRB exile David Bell, and his weekly the Irish Republic. In contrast to Roberts, Bell, committed to black suffrage and to Reconstruction, was allied to the Republicans and was calling a "cleansing" of the spirits of the Irish in America: "Let our people fling off the scales of bigotry and declare that all men are entitled to 'life, liberty, and happiness.'"[9]

John Devoy records that, in the course of 1866, various conferences to reunite the various factions were held. Their efforts were to elect James Stephens as president of a united organisation. Stephens had escaped the round-up of the IRB leadership in Dublin the previous year, but still promised that "The Irish flag—the flag of the Irish Republic—will float in an Irish breeze before New Year's Day, 1867." At the close of 1866, a conference of the refugees of the IRB and many of the American officers who had been in Ireland was held in New York and presided over by Stephens, at which the decision was taken that the fight should be made early in 1867. Some thousands of rifles were afterwards sent to Ireland, but arrived too late to be of any use in the Rising.[10]

-

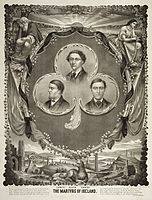

Three Manchester Martyrs of 1867; at right is Michael O'Brien a former Corporal of Battery E 1st New Jersey Artillery regiment

-

Fenian convicts escape from Fremantle in the 1876 Catalpa rescue.

Canada

[edit]

In Canada, Fenian is used to designate a group of Irish radicals, a.k.a. the American branch of the Fenian Brotherhood in the 1860s. They made several attempts to invade some parts of the British colonies of New Brunswick (i.e., Campobello Island) and Canada (present-day Southern Ontario and Missisquoi County[11]), with the raids continuing after these colonies had been confederated. The ultimate goal of the Fenian raids was to hold Canada hostage and therefore be in a position to blackmail the United Kingdom to give Ireland its independence. Because of the invasion attempts, support or collaboration for the Fenians in Canada became very rare even among the Irish.

Francis Bernard McNamee, the man who started the Fenian movement in Montreal (and who was later suspected of being a government spy), was a case in point. In public, he proclaimed his loyalty to the queen and called for an Irish militia company to defend Canada against the Fenians. In private, he wrote that the real purpose of an Irish militia company would be to assist the Fenian invasion, adding for good measure that if the government denied his request he would raise the cry of anti-Irish Catholic discrimination and bring more of his aggrieved countrymen into the Fenian Brotherhood.[12]

A suspected Fenian, Patrick J. Whelan, was hanged in Ottawa for the assassination of Irish Canadian politician, Thomas D'Arcy McGee in 1868, who had been a member of the Irish Confederation in the 1840s.

The danger posed by the Fenian raids was an important element in motivating the British North America colonies to consider a more centralised defence for mutual protection, ultimately realised through Canadian Confederation.

England

[edit]

The Fenians in England and the British Empire were a major threat to political stability. In the late 1860s, the IRB control centre was in Lancashire. In 1868, the Supreme Council of the IRB, the provisional government of the Irish Republic, was restructured. The four Irish provinces (Connacht, Leinster, Ulster and Munster), along with Scotland, the north and south of England and London, had representatives on the council. Later four honorary members were co-opted. The Council elected three members to the executive. The President was chairman, the Treasurer managed recruitment and finance, and the Secretary was director of operations. There were IRB Circles in every major city in England.[13]

On 23 November 1867,[14] three Fenians, William Philip Allen, Michael O'Brian, and Michael Larkin,[15] known as the Manchester Martyrs, were executed in Salford for their attack on a police van to release Fenians held captive earlier that year.[16]

On 13 December 1867, the Fenians exploded a bomb in attempt to free one of their members being held on remand at Clerkenwell Prison in London. The explosion damaged nearby houses, killed 12 people and caused 120 injuries. None of the prisoners escaped. The bombing was later described as the most infamous action carried out by the Fenians in Great Britain in the 19th century. It enraged the public, causing a backlash of hostility in Britain which undermined efforts to establish home rule or independence for Ireland. The IRB Supreme Council condemned the bombing.[17]

The Fenians also exploded three bombs on the London Underground in 1883–1885 and were also believed to be responsible for a bomb on 26 April 1897 at Aldersgate Street station which fatally injured two people.[18]

Australia

[edit]In 1868, an Irishman, Henry James O'Farrell, attempted to assassinate the Duke of Edinburgh, second son of Queen Victoria, who was visiting Sydney. O'Farrell claimed to be a Fenian but was probably a lone actor. He was hanged on 21 April 1868. The Duke recovered but the attack was used by politician Henry Parkes to wage a sectarian campaign against Catholics and people of Irish origin.[19]

Later in 1868, the Hougoumont, the last convict ship to Australia, arrived in Western Australia carrying 62 Fenian prisoners convicted in England. Over the next decade, most were released and many chose to go to America. By 1876 only six remained in custody, and in that year they were freed in a daring rescue mission organised by the IRB in the United States. The ship Catalpa was sailed from New Bedford, Massachusetts, to Fremantle, Western Australia, a distance of some 12,000 miles, and took the men back to the United States. The rescue caused a worldwide sensation and sparked several ballads.[20]

Contemporary usage

[edit]Northern Ireland

[edit]In Northern Ireland, Fenian is used by some as a derogatory word for Irish Catholics;[21][22] in 2012, British National Party leader Nick Griffin was criticised by Unionists and Republicans for tweeting the term while attending an Ulster Covenant event at Stormont, Belfast; Griffin referred to Lambeg drums, saying "the bodran [sic] can't match the lambeg, you Fenian bastards".[23][24]

Scotland

[edit]

The term Fenian is used similarly in Scotland. During Scottish football matches, it is often aimed in a sectarian manner at supporters of Celtic F.C.[25] Celtic has its roots in Glasgow's immigrant Catholic Irish population and the club has thus been associated with Irish nationalism, symbolised by the almost universal flying of the Irish Tricolour during matches. Other Scottish clubs that have Irish roots, such as Hibernian and Dundee United, do not tend to have the term applied to them, however.[26] The term is now firmly rooted within the Old Firm rivalry between Celtic and Rangers.[27] Use of the term as a religious slur carried criminal penalties in some contexts under the Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act 2012, before its repeal in January 2018.

The use of Fenian as a term of abuse has also been documented when Celtic play outside Scotland. In 2013, AFC Ajax was fined €25,000 by UEFA when its supporters displayed a banner reading "Fenian Bastards" at a match between the sides at the Amsterdam Arena on 6 November that year.[28] The term was also used in an anti-Irish banner unfurled by Lazio supporters at a Champions League match against Celtic on 28 November 2023.[29]

Australia

[edit]In Australia, Fenian is used as a pejorative term for those members of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) who have Australian Republican views similar to those who support Irish unification. In a speech given at the ALP Convention in Adelaide on 15 October 2006, Michael Atkinson, Attorney-General of South Australia, spoke of those members of the ALP who wished to remove the title Queen's Counsel and other references to the crown as "Fenians and Bolsheviks". Atkinson made a further mention of Fenianism when the title of Queen's Counsel was abolished. The title of Queen's Counsel was re-instated by the South Australian government in 2019.[30]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "Fenians". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Green, E. R. R. (October 1958). "The Fenians". History Today. Vol. 8, no. 10. pp. 698–705.

- ^ Ryan, p. 318

- ^ "Fianna". www.timelessmyths.com. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ McGee, pp. 13–14

- ^ Kennerk, Barry (2010). Shadow of the Brotherhood: The Temple Bar Shootings. Mercier Press. ISBN 978-1-8563-5677-0.

- ^ "Fenian Brotherhood". IrishRepublicanHistory. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ Montgomery, David (1967). Beyond Equality: Labor and the Radical Republicans, 1862–1872. New York: Alfred Knopf. pp. 130–133. ISBN 978-0252008696. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Knight, Matthew (2017). "The Irish Republic: Reconstructing Liberty, Right Principles, and the Fenian Brotherhood". Éire-Ireland (Irish-American Cultural Institute). 52 (3 & 4): 252–271. doi:10.1353/eir.2017.0029. S2CID 159525524. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Devoy, John (1929). Recollections of an Irish rebel.... A personal narrative by John Devoy. New York: Chas. P. Young Co., printers. p. 276. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "For the Sake of Ireland: The Fenian Raids of Missisquoi County 1866 & 1870". townshipsheritage.com.

- ^ Further reading: W. D'Arcy, The Fenian movement in the United States: 1858–1886 (New York, 1947, 1971). W.S. Neidhardt, Fenianism in North America (Pennsylvania, 1975). H. Senior, The Fenians and Canada (Toronto, 1978). D.A. Wilson, Thomas D'Arcy McGee, vol. I: passion, reason, and politics, 1825–57 (Montreal and Kingston, 2008).

- ^ Stanford, Jane (2011). That Irishman. The History Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-84588-698-1.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Dock and the Scaffold, by Unknown". www.ibiblio.org.

- ^ In Memoriam, William Philip Allen, Michael O'Brien, and Michael Larkin [original missing], 1867. Box 1, Folder 9, Allen Family Papers, 1867, AIS.1977.14, Archives Service Center, University of Pittsburgh

- ^ Allen Family Papers, 1867, AIS.1977.14, Archives Service Center, University of Pittsburgh

- ^ Jane Stanford, That Irishman: the life and times of John O’Connor Power, History Press Ireland, 2011, p. 31, endnotes, 43,44

- ^ Alan A Jackson (1986). London's Metropolitan Railway. David & Charles, Newton Abbot. p. 123. ISBN 0-7153-8839-8.

- ^ Travers, Robert (1986). The Phantom Fenians of New South Wales. Sydney: Intl Specialized Book Service.

- ^ Amos, Keith (1988). The Fenians in Australia 1865–1880. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

- ^ Croft, Hazel. "Orangemen and Loyalists target Catholics". Socialist Worker. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011.

- ^ "Fenian". TheFreeDictionary.com.

- ^ Rutherford, Adrian; O'Hara, Victoria (2 October 2012). "BNP leader Nick Griffin faces police probe over 'fenian bastards' sectarian tweet during procession". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ "BNP leader Nick Griffin defends Fenian comment on Twitter". BBC News. Northern Ireland. 30 September 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ "Ibrox chant ruling goes to appeal". BBC News. 18 April 2006.

- ^ Bradley, Joseph (1998). Fanatics!: power, identity, and fandom in football. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0415181037.

- ^ Devine, Tom (1996). Scotland in the twentieth century. ISBN 978-0748608393.

The divide between Orange and Green has been increasingly transformed into a divide between Blue and Green

- ^ "Ajax fined £21,000 for banner at Celtic match". Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ "'The famine is over go home f***ing potato eaters' – Lazio fans unfurl huge anti-Irish banners at Celtic game in Rome". Belfasttelegraph.co.uk. 29 November 2023.

- ^ Gout, Hendrik (9 May 2008). "Rann usurps Atkinson over Queen's Counsels". InDaily. Archived from the original on 5 August 2008.

References

[edit]- Comerford, R.V. The Fenians in Context: Irish Politics & Society 1848–82, Dublin: Wolfhound Press, 1985.

- Cronin, Seán. The McGarrity Papers, Anvil Books, Ireland, 1972

- Green, E. R. R. "The Fenians" History Today (Oct. 1958) 8#10 pp 698–705.

- Kee, Robert. The Bold Fenian Men, Quartet Books (London 1976), ISBN 0-7043-3096-2

- Kelly, M. J. The Fenian Ideal and Irish Nationalism, 1882–1916, Boydell and Brewer, 2006, ISBN 1-84383-445-6

- Kenny, Michael. The Fenians, The National Museum of Ireland in association with Country House, Dublin, 1994, ISBN 0-946172-42-0

- McGee, Owen. The IRB: The Irish Republican Brotherhood from The Land League to Sinn Féin, Four Courts Press, 2005, ISBN 1-85182-972-5

- Ó Broin, Leon. Fenian Fever: An Anglo-American Dilemma, Chatto & Windus, London, 1971, ISBN 0-7011-1749-4.

- O'Hegarty, P. S. A History of Ireland Under the Union, Methuen & Co. (London 1952).

- Quinlavin, Patrick, and Paul Rose, The Fenians in England (London, 1982).

- Ramón, Marta. A Provisional Dictator: James Stephens and the Fenian Movement, University College Dublin Press (2007), ISBN 978-1-904558-64-4

- Ryan, Desmond. The Fenian Chief: A Biography of James Stephens, Hely Thom LTD, Dublin, 1967

- Ryan, Mark F. Fenian Memories, Edited by T.F. O'Sullivan, M. H. Gill & Son, LTD, Dublin, 1945

- Snay, Mitchell. Fenians, Freedmen, and Southern Whites: Race and Nationality in the Era of Reconstruction (2010)

- Stanford, Jane. That Irishman: The Life and Times of John O'Connor Power, The History Press Ireland, Dublin 2011, ISBN 978-1-84588-698-1

- Steward, Patrick, and Bryan McGowan. The Fenians: Irish Rebellion in the North Atlantic World, 1858–1876. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2013.

- Thompson, Francis John (1936). Francis J. Thompson Diary (PDF).[permanent dead link] A journal of Francis Thompson's research into Fenianism and the Celtic Renaissance.

- Thompson, Francis John (1940). Fenianism and the Celtic Renaissance (PDF) (Ph.D.). New York: New York University.

- Ui Fhlannagain, Fionnuala. Finini Mheiricea agus an Ghaeilge, Binn Éadair, Baile Átha Cliath (Howth, Dublin), Ireland: Coiscéim, 2008, OCLC 305144100

- Whelehan, Niall. The Dynamiters: Irish Nationalism and Political Violence in the Wider World, 1867–1900 (Cambridge, 2012).

Further reading

[edit]- Brady, William Maziere (1883). (1st ed.). London: Robert Washbourne.

External links

[edit]- Fenians.org

- Fenian Brotherhood

- BBC History article on the Irish Republican Brotherhood

- 1865 newspaper Article describing the Fenians

- History Learning Site > Ireland 1848 to 1922 > The Fenian Movement

- The Fenian Movement in the US including digitised materials about their activities. From the Immigration to the United States, 1789–1930 collection, Harvard University Library Open Collections Program