Walkabout (film)

| Walkabout | |

|---|---|

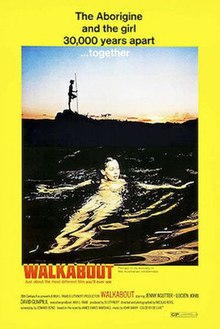

American release poster | |

| Directed by | Nicolas Roeg |

| Screenplay by | Edward Bond |

| Based on | Walkabout by James Vance Marshall |

| Produced by | Si Litvinoff |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Nicolas Roeg |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | John Barry |

Production company | Max L. Raab-Si Litvinoff Films |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release dates | |

Running time | 100 minutes[2] |

| Countries | |

| Language | English[2] |

| Budget | A$1 million[3] |

Walkabout is a 1971 adventure survival film directed by Nicolas Roeg and starring Jenny Agutter, Luc Roeg, and David Gulpilil. Edward Bond wrote the screenplay, which is loosely based on the 1959 novel by James Vance Marshall. It centres on two white schoolchildren who are left to fend for themselves in the Australian Outback and who come across a teenage Aboriginal boy who helps them to survive.

Roeg's second feature film, Walkabout was released internationally by 20th Century Fox, and was one of the first films in the Australian New Wave cinema movement. Alongside Wake in Fright, it was one of two Australian films entered in competition for the Grand Prix du Festival at the 1971 Cannes Film Festival.[4] It was subsequently released in the United States in July 1971, and in Australia in December 1971.

In 2005, the British Film Institute included it in their list of the "50 films you should see by the age of 14".

Plot

[edit]A teenage girl and her younger brother live with their parents in a modest high rise apartment in Sydney. One day their father drives them into the Outback, still in their school uniforms, ostensibly for a picnic. As they prepare to eat, the father draws a gun and fires at the children. The boy believes it to be a game, but the daughter realises her father is attempting to murder them, and flees with her brother, seeking shelter behind rocks. She watches as her father sets their car on fire and shoots himself in the head. The girl conceals the suicide from her brother, retrieves some of the picnic food, and leads him away from the scene, attempting to walk home through the desert.

By the middle of the next day, they are weak and the boy can barely walk. Discovering an oasis with a small water hole and a fruit tree, they spend the day playing, bathing, and resting. By the next morning, the water has dried up. They are then discovered by an Aboriginal boy. He does not speak English, much to the girl's frustration, but her brother mimes their need for water and the newcomer cheerfully shows them how to draw it from the drying bed of the oasis. The three travel together, with the Aboriginal boy sharing kangaroo meat he has caught from hunting. The boys learn to communicate to some extent using words from each other's languages and gestures; the girl makes no such attempts.

While in the vicinity of a plantation, a white woman walks past the Aboriginal boy, who simply ignores her when she speaks to him. She appears to see the other children, but they do not see her, and they continue on their journey. The children also discover a weather balloon belonging to a nearby research team working in the desert. After drawing markings of a modern-style house, the Aboriginal boy eventually leads them to an abandoned farm, and takes the small boy to a nearby road. The Aboriginal boy hunts down a water buffalo and is wrestling it to the ground when two white hunters appear in a truck and nearly run him over. He watches in shock as they wantonly shoot several buffalo with a rifle. The boy then returns to the farm, but passes by without speaking.

Later, the Aboriginal boy lies in a trance among a slew of buffalo bones, having painted himself in ceremonial markings. He returns to the farmhouse, catching the undressing girl by surprise, and initiates a courtship ritual, performing a dance in front of her.[5] Although he dances outside all day and into the night until he becomes exhausted, she is frightened and hides from him, and tells her brother they will leave him the next day. In the morning, after they dress in their school uniforms, the brother takes her to the Aboriginal boy's body, hanging in a tree. Showing little emotion, the girl wipes ants from the dead boy's chest. Hiking up the road, the siblings find a nearly-deserted mining town where a surly employee directs them towards nearby accommodation.

Years later, a man arrives home from work as the now adult girl prepares dinner. While he embraces her and relates office gossip, she either imagines or remembers a time in which she, her brother, and the Aboriginal boy are playing and swimming naked in a billabong in the Outback.

Cast

[edit]- Jenny Agutter as Girl

- Luc Roeg (credited as Lucien John) as White Boy[6]

- David Gulpilil (miscredited as David Gumpilil) as Black Boy

- John Meillon as Father

- Robert McDarra as Man

- Pete Carver as No Hoper

- John Illingsworth as Husband

- Hilary Bamberger as Woman

- Barry Donnelly as Australian Scientist

- Noeline Brown as German Scientist

- Carlo Manchini as Italian Scientist

None of the characters are named.

Themes

[edit]Roeg described the film in 1998 as "a simple story about life and being alive, not covered with sophistry but addressing the most basic human themes; birth, death, mutability".[7]

Agutter regards the film as multilayered, in one regard being a story about children lost in the Outback finding their way, and, in the other, an allegorical tale about modern society and the loss of innocence.[8] The Australian filmmaker Louis Nowra noted that biblical imagery runs throughout the film; in one scene there is a cut to a subliminal flashback of the father's suicide, but the scene plays in reverse and the father rises up as if he has been "resurrected". Many writers have also drawn a direct parallel between the depiction of the Outback and the Garden of Eden, with Nowra observing that this went as far as to include "portents of a snake slithering across the bare branches of the tree" above Agutter's character as she sleeps.[9]

Gregory Stephens, an associate professor of English, sees the film framed as a typical "back to Eden" story, including common motifs from 1960s counterculture; he offers the skinny-dipping sequence as an example of a "symbolic shedding of the clothes of the over-civilized world".[10] By way of the girl's rejection of the Aboriginal boy and his subsequent death the film paints the Outback as "an Eden that can only ever be lost".[11] Agutter shares a similar interpretation, noting, "We cannot go back and have that Garden of Eden. We cannot go back and make it innocent again." She considers the ages of the two adolescents, who are on the cusp of adulthood and losing their childhood innocence, as a metaphor for the irreversible change wrought by Western civilisation.[8]

Production

[edit]The film was the second feature directed by Nicolas Roeg, a British filmmaker. He had long planned to make a film of the novel Walkabout, in which the children are Americans stranded by a plane crash. After the indigenous boy finds and leads them to safety, he dies of influenza contracted from them, as he has not been immunised. Roeg approached the English playwright Edward Bond about writing the script, who handed in fourteen pages of handwritten notes. Roeg was impressed, and Bond expanded his treatment into a 63-page screenplay.[12] Roeg then obtained backing from two American businessmen, Max Raab and Si Litvinoff,[13] who incorporated a company in Australia and sold the distribution rights to 20th Century Fox.[14]

Filming began in Sydney in August 1969 and later moved to Alice Springs,[3] and Roeg's son, Luc, played the younger boy in the film. Roeg brought an outsider's eye and interpretation to the Australian setting, and improvised greatly during filming. He commented, "We didn't really plan anything—we just came across things by chance…filming whatever we found."[15] The film is an example of Roeg's well-defined directorial style, characterised by strong visual composition from his experience as a cinematographer, combined with extensive cross-cutting and the juxtaposition of events, location, or environments to build his themes.[16] The music was composed and conducted by John Barry, and produced by Phil Ramone,[17] and the poem read at the end of the film is Poem 40 from A. E. Housman's A Shropshire Lad.[18]

About her nude swimming scene, Jenny Agutter said, "Nic wanted the scene in which I swam naked to be straightforward. He wanted me to be uninhibited – which I wasn't. I was a very inhibited young woman. I didn't feel uncomfortable about the intention of the scene, but that doesn't make you feel any better. There was no one around, apart from Nic in the distance with his camera. No lights, nothing. Once he'd got the shot, I got out of the water and dressed as quickly as possible."[19] Agutter has stated she does not regret filming the scenes, but regrets how they have been taken out of context and uploaded to the internet by "perverts".[20]

The British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) surmised Agutter was seventeen years old at the time of filming (she was actually sixteen when filming began in July 1969[13]), and therefore the scenes did not pose a problem when submitted to the BBFC in 1971 and later in 1998. The Protection of Children Act 1978 prohibited distribution and possession of indecent images of people under the age of sixteen so the issue of potential indecency had not been considered on previous occasions. However, the Sexual Offences Act 2003 raised the age threshold to eighteen which meant the BBFC was required to consider the scenes of nudity in the context of the new law when the film was re-submitted in 2011. The BBFC reviewed the scenes and considered them not to be indecent and passed the film uncut.[2]

The film features several scenes of animal hunting and killing, such as a kangaroo being speared and bludgeoned to death. The Cinematograph Films (Animals) Act 1937 makes it illegal in the United Kingdom to distribute or exhibit material where the production involved inflicting pain or terror on an animal. Since the animals did not appear to suffer or be in distress the film was deemed not to contravene the Act.[2]

Reception

[edit]Walkabout fared poorly at the box office in Australia. Critics debated whether it could be considered an Australian film, and whether it was an embrace of or a reaction to the country's cultural and natural context.[15] In the US, the film was originally rated R by the MPAA due to nudity, but was reduced to a GP-rating (PG) on appeal.

Critic Roger Ebert called it "one of the great films".[21][22] He writes that it contains little moral or emotional judgement of its characters, and ultimately is a portrait of isolation in proximity. At the time, he stated: "Is it a parable about noble savages and the crushed spirits of city dwellers? That's what the film's surface suggests, but I think it's about something deeper and more elusive: the mystery of communication."[22] Film critic Edward Guthmann also notes the strong use of exotic natural images, calling them a "chorus of lizards".[23] In Walkabout, an analysis of the film, author Louis Nowra wrote: "I was stunned. The images of the Outback were of an almost hallucinogenic intensity. Instead of the desert and bush being infused with a dull monotony, everything seemed acute, shrill, and incandescent. The Outback was beautiful and haunting."[24] Writer and filmmaker Alex Garland characterised the film as "virtuoso filmmaking".[25]

More than 50 years after its release, review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes surveyed 42 critics and judged 86 per cent of the reviews to be positive, with an average rating of 8.2 out of 10.[26] In the 2012 BFI survey of the world's greatest films, Walkabout featured in four critics' and four directors' choices of their favourite films.[27]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Walkabout: Movie Details". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Walkabout". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ a b Pike & Cooper 1998, p. 258.

- ^

"Official Selection 1971". Festival de Cannes. France. Archived from the original on 2 December 2010.

Official Selection 1971....Walkabout directed by Nicolas Roeg

- ^ Roeg 1998, 1:20:00.

- ^ Mawston, Mark. "Talkabout Walkabout". Cinema Retro. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Danielsen, Shane (27 March 1998). "Walkabout: An Outsider's Vision Endures". The Australian.

- ^ a b Agutter, Jenny. "Jenny Agutter on Walkabout" (Interview). The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 13 November 2019 – via YouTube.

It has to be that particular age [adolescence of the European girl and the aboriginal boy] where the innocence is just going. Because of course what Nick Roeg... Nick Roeg is talking about many things – the film has lots of layers to it. There is the story about children lost in the Outback, finding their way. There is a story about society and the loss of innocence. And the film is about losing one's innocence and not being able to go back, once you have gone to a certain stage. And that is our Western society: we go to a certain place, and then we are spoiled, we are changed. Whatever it is, we cannot go back and have that Garden of Eden. We cannot go back and make it innocent again. We cannot go back once we have got to a certain stage.

[time needed][excessive quote] - ^ Nowra 2003, p. 36.

- ^ Stephens 2018, p. 142.

- ^ Goldsmith & Lealand 2010, p. 210.

- ^ Nowra 2003, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Nowra 2003, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Nowra 2003, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Fiona Harma (2001). "Walkabout". The Oz Film Database. Murdoch University. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ Chuck Kleinhans. "Nicholas Roeg—Permutations without profundity". Jump Cut. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ Nowra 2003, p. 85.

- ^ Nowra 2003, p. 62.

- ^ Godfrey, Alex (9 August 2016). "How we made Walkabout". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Stolworthy, Jacob (9 July 2022). "Jenny Agutter says she has one 'regret' about doing Walkabout nude scene when she was 16". The Independent. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (13 April 1997). "Walkabout (1971)". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger. "Walkabout by Nicolas Roeg". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ Guthmann, Edward (3 January 1997). "Intriguing Walkabout in the Past". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ Nowra 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Kemp, Sam (4 February 2023). "Walkabout: the movie Alex Garland calls 'virtuoso filmmaking'". Far Out. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ Walkabout at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ Walkabout at BFI

Sources

[edit]- Goldsmith, Ben; Lealand, Geoffrey, eds. (2010). Australia and New Zealand. Directory of world cinema. Bristol, England: Intellect Books. ISBN 978-1-841-50373-8.

- Nowra, Louis (2003). Walkabout. Australian Screen Classics. London, England: Currency Press. ISBN 978-0-868-19700-5.

- Pike, Andrew; Cooper, Ross (1998). Australian Film 1900–1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-54332-2.

- Roeg, Nicolas (1998). Walkabout (Audio commentary). United States: The Criterion Collection. ISBN 0780020847.

- Stephens, Gregory (2018). Trilogies as Cultural Analysis: Literary Re-imaginings of Sea Crossings, Animals, and Fathering. Cambridge, England: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-527-51911-4.

External links

[edit]- Walkabout at IMDb

- Walkabout at AllMovie

- Walkabout at Metacritic

- Walkabout: Landscapes of Memory an essay by Paul Ryan at The Criterion Collection

- Walkabout Q & A with Nic Roeg, Lucien Roeg and Jenny Agutter at BFI in 2011

- Walkabout at Oz Movies

- 1971 films

- 1970s adventure drama films

- 1970s Australian films

- 1970s British films

- 1970s English-language films

- 20th Century Fox films

- Australian adventure drama films

- British adventure drama films

- British survival films

- English-language adventure drama films

- Fiction about familicide

- Films about Aboriginal Australians

- Films about hunters

- Films about siblings

- Films based on British novels

- Films directed by Nicolas Roeg

- Films scored by John Barry (composer)

- Films set in deserts

- Films set in the Outback

- Films shot in the Northern Territory

- Films with screenplays by Edward Bond

- Obscenity controversies in film