Short squeeze

In the stock market, a short squeeze is a rapid increase in the price of a stock owing primarily to an excess of short selling of a stock rather than underlying fundamentals. A short squeeze occurs when demand has increased relative to supply because short sellers have to buy stock to cover their short positions.[1]

Overview

[edit]Short selling is a finance practice in which an investor, known as the short-seller, borrows shares and immediately sells them, hoping to buy them back later ("covering") at a lower price. As the shares were borrowed, the short-seller must eventually return them to the lender (plus interest and dividend, if any), and therefore makes a profit if they spend less buying back the shares than they received when selling them. However, an unexpected piece of favorable news can cause a jump in the stock's share price, resulting in a loss rather than a profit. Short-sellers might then be triggered to buy the shares they had borrowed at a higher price, in an effort to keep their losses from mounting should the share price rise further.

Short squeezes result when short sellers of a stock move to cover their positions, purchasing large volumes of stock relative to the market volume. Purchasing the stock to cover their short positions raises the price of the shorted stock, thus triggering more short sellers to cover their positions by buying the stock; i.e., there is increasing demand. This dynamic can result in a cascade of stock purchases and an even bigger jump of the share price.[2][3] Borrow, buy and sell timing can lead to more than 100% of a company's shares sold short.[4][5] This does not necessarily imply naked short selling, since shorted shares are put back onto the market, potentially allowing the same share to be borrowed multiple times.[6]

Short squeezes tend to happen in stocks that have expensive borrow rates. Expensive borrow rates can increase the pressure on short sellers to cover their positions, further adding to the reflexive nature of this phenomenon.

Buying by short sellers can occur if the price has risen to a point where shorts receive margin calls that they cannot (or choose not to) meet, triggering them to purchase stock to return to the owners from whom (via a broker) they had borrowed the stock in establishing their position. This buying may proceed automatically, for example if the short sellers had previously placed stop-loss orders with their brokers to prepare for this possibility. Alternatively, short sellers simply deciding to cut their losses and get out (rather than lacking collateral funds to meet their margin) can cause a squeeze. Short squeezes can also occur when the demand from short sellers outweighs the supply of shares to borrow, which results in the failure of borrow requests from prime brokers. This sometimes happens with companies that are on the verge of filing for bankruptcy.

Targets for short squeezes

[edit]Short squeezes are more likely to occur in stocks with relatively few traded shares and commensurately small market capitalization and float. Squeezes can, however, involve large stocks and billions of dollars. Short squeezes may also be more likely to occur when a large percentage of a stock's float is short, and when large portions of the stock are held by people not tempted to sell.[7]

Short squeezes can also be facilitated by the availability of inexpensive call options on the underlying security because they add considerable leverage. Typically, out of the money options with a short time to expiration are used to maximize the leverage and the impact of the squeezer's actions on short sellers. Call options on securities that have low implied volatility are also less expensive and more impactful. (A successful short squeeze will dramatically increase implied volatility).[8]

Long squeeze

[edit]The opposite of a short squeeze is the less common long squeeze. A squeeze can also occur with futures contracts, especially in agricultural commodities, for which supply is inherently limited.[9]

Gamma squeeze

[edit]The sale of naked call options creates a short position for the seller, in which the seller's loss increases with the price of the underlying asset and is therefore potentially unlimited. Sellers have the option of hedging their position by, among other things, buying the underlying asset at a known price at any time before the option is exercised, converting their naked calls into covered calls. By buying calls, per unit of capital invested, the buyer can create a larger upward pressure on the price of the underlying than they could by buying shares: this pressure is in fact realized when the seller purchases the underlying, and is greater if the seller invests more capital hedging their position by buying the (expensive) underlying than the buyer invests to purchase the (inexpensive) calls.

The resulting upward pressure on the price of the underlying can develop into a positive feedback loop, as call-sellers react to the rising price by buying the underlying to avoid exposure to the risk that its price may rise further.[10]

Examples

[edit]In May 1901, James J. Hill and J. P. Morgan battled with E. H. Harriman over control of the Northern Pacific Railway. By the end of business on May 7, 1901, the two parties controlled over 94% of outstanding Northern Pacific shares. The resulting runup in share price was accompanied by frenetic short selling of Northern Pacific by third parties. On May 8, it became apparent that uncommitted NP shares were insufficient to cover the outstanding short positions, and that neither Hill and Morgan nor Harriman were willing to sell. This triggered a sell-off in the rest of the market as NP "shorts" liquidated holdings in an effort to raise cash to buy NP shares to meet their obligations. The ensuing stock market crash, known as the Panic of 1901, was partially ameliorated by a truce between Hill/Morgan and Harriman.[11]

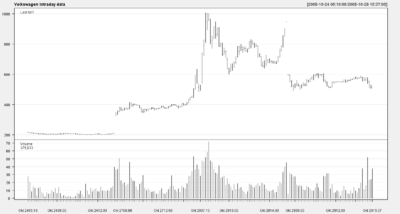

In October 2008, a short squeeze triggered by an attempted takeover by Porsche temporarily drove the shares of Volkswagen AG on the Xetra DAX from €210.85 to over €1000 in less than two days, briefly making it the most valuable company in the world.[12][13] Then-Porsche CEO Wendelin Wiedeking was charged with market manipulation but was acquitted by a Stuttgart court.[14][15]

In 2012, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission charged Philip Falcone with market manipulation in relation to a short squeeze on a series of high-yield bonds issued by MAAX Holdings. After hearing that a firm was shorting the bonds, Falcone purchased the entire issue of bonds. He also lent the bonds to the short-sellers, and then bought them back when the traders sold them. As a result, his total exposure exceeded the entire issue of the MAAX bonds. Falcone then stopped lending the bonds, so that short-sellers could not liquidate their positions anymore. The price of the bonds rose dramatically.[16][17] The short-sellers could only liquidate their positions by contacting Falcone directly.[17]

In November 2015, Martin Shkreli orchestrated a short squeeze on failed biotech KaloBios (KBIO) that caused its share price to rise by 10,000% in just five trading days. KBIO had been perceived by short sellers as a "no-brainer near-term zero".[18]

The GameStop short squeeze, starting in January 2021, was a short squeeze occurring on shares of GameStop,[19][20] primarily triggered by the Reddit forum WallStreetBets.[21][22] This squeeze led to the share price reaching an all-time intraday high of US$483 on January 28, 2021 on the NYSE.[23][24] This squeeze caught the attention of many news networks and social media platforms.[25]

In March 2022, a short squeeze was initiated on nickel contracts on the London Metal Exchange (LME). In the months prior, industrialist Xiang Guangda took a large short position on LME nickel, but a rise in nickel prices following the Russian invasion of Ukraine forced Guangda make significant purchases to cover his position, causing LME nickel prices to rise by around 250 percent. On paper this would've caused Guangda billions of dollars of losses, but the LME halted all trading on nickel contracts and reversed many of the trades which occurred during the squeeze, shielding Guangda from much of the loss.[26][27][28]

See also

[edit]- Short interest ratio

- Stock market crash – a short squeeze is effectively a reverse crash

References

[edit]- ^ "Short Squeeze". Archived from the original on 2010-09-18. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ^ Constable, Simon (6 December 2015). "What Is a Short Squeeze?". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ Powell, Jamie (25 January 2021). "GameStop can't stop going up". FT Alphaville. Archived from the original on 2022-12-10. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ Caplinger, Dan Yes, a Stock Can Have Short Interest Over 100 Percent The Motley Fool, Jan 2021

- ^ Sizemore, Charles Lewis What Exactly Is a Short Squeeze? Kiplinger, January 28, 2021

- ^ Planes, Alex (9 March 2020). "This Is the Most Shorted Stock in the Market Right Now". The Motley Fool. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Short Squeezes". Investors Underground. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- ^ "Options Helped Fuel the GameStop Stock Squeeze. Here's How That Works". Barron's. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ Thomas, John (13 September 2010). "A Short Squeeze In Corn May Hit The Market". OilPrice.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Aggarwal, DK. "What happens when stock prices shoot up because of Gamma Squeeze". The Economic Times. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Low, Peter (2010). "The Northern Pacific Panic of 1901". Financial History. Museum of American Finance.

- ^ Gow, David (29 October 2009). "Porsche makes more VW stock available to desperate short-sellers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Krstić, Ivan (7 January 2009). "How Porsche hacked the financial system and made a killing". Archived from the original on 2010-08-15. Retrieved 2010-11-25.

- ^ "Freispruch für Wiedeking rechtskräftig". Spiegel Online. 2016-07-28. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- ^ Böcking, David (18 March 2016). "Freispruch für die Porsche-Zocker". Spiegel. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ Henning, Peter J. (28 June 2012). "In Case Against Philip Falcone, a Warning to Others". New York Times. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ a b Levine, Matt (26 January 2021). "GameStop Is Just a Game". Bloomberg Opinion. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ "How Martin Shkreli caused a 10,000% squeeze on KBIO". Mox Reports. August 1, 2018. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Connor. "Short Squeeze Sends GameStop Shares to 2007 Levels. What Happens Next". Barrons. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Ferré, Ines. "GameStop shares soar 50% as massive short squeeze forges ahead". Yahoo! Sports. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Li, Yun (January 27, 2021). "GameStop mania explained: How the Reddit retail trading crowd ran over Wall Street pros". CNBC. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ D'Anastasio, Cecilia. "A Fight Over GameStop's Soaring Stock Turns Ugly". Wired. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ "NYSE GAMESTOP CORPORATION GME". www.nyse.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ McCabe, Caitlin; Ostroff, Caitlin (May 26, 2021). "GameStop, AMC Entertainment Shares Soar as Meme Stock Rally Returns". www.wsj.com.

- ^ Phillips, Matt; Lorenz, Taylor (2021-01-27). "'Dumb Money' Is on GameStop, and It's Beating Wall Street at Its Own Game". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-04-06.

- ^ Hume, Neil; Lockett, Hudson; Olcott, Eleanor; Li, Gloria (11 March 2022). "Xiang Guangda, the metals 'visionary' who brought the nickel market to a standstill". Financial Times. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ The Editorial Board (2022-03-22). "Opinion | A Chinese Nickel Market Mystery". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2022-11-16.

- ^ ""Big Shot's" Nickel Short Squeeze: Who is Xiang Guangda?". finews.asia. 10 March 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2022.